Speech inaugurating a new tombstone for Károly Kertbeny (1824-1882)

given in Budapest, June 29th, 2002

120 years ago the same man was commemorated in this cemetery as follows: "He devoted his life to serving his country, even when he was living abroad. He publicised our glory there among foreign peoples. His first literary activities were received with mockery, but he did not give up and he brought light to Hungarian literature for foreign people." (József Komócsy 1882)

35 years later, in 1917, a Hungarian writer, Lajos Hatvany referred to Kertbeny in this way: "this moody, fluttering, imperfect writer is one of the best and undeservedly forgotten Hungarian memoire writers".

Today we gathered here to pay our respects to the works of Kertbeny - as we can state with certainty that he created something lasting he longed for his whole life.

Kertbeny Károly Mária - or in his original name Karl Maria Benkert - was born in Vienna on the 28th of February in 1824 - according to his autobiographical notes - "as a son of Hungarian parents". He moved to Hungary with his family in 1826, and changed his name from Benkert to Kertbeny in 1847. Between 1846 and 1875 he criss-crossed Europe and returned to Hungary in 1875 where the old, ill writer was provided with an apartment in the Rudas bath house by the city of Budapest. Kertbeny died on the 23rd of January in 1882: he did not have any relatives so he was buried at the expense of the writers' mutual society.

In Hungarian literary history he is remembered as a not too significant translator and writer whose greatest literary merit was the enthusiastic intention to popularise Hungarian literature abroad, particularly in German speaking countries.

Kertbeny's life was characterised by dualisms. According to some, he did not only have a double name but also a double nature: "He was born effeminately sensitive, soft, believing, fair, open minded and enthusiastic for beauty. He loved to love, and loved to be loved. He loved only the beautiful and he wanted the love of the best. Mária! - An old, vain, swindling, naughty, clownish, thick skinned, envious, literary adventurer became of him: Károly, poor, Károly!" (Hatvany)

Kertbeny was born in Vienna, his mother tongue was German, but he declared himself Hungarian: "I was born in Vienna, yet I am not a Viennese, but rightfully Hungarian", he wrote in a letter in 1880. He clearly had great literary ambitions but in anonymously published political pamphlets he broke a lance for the rights of homosexuals and constructed a whole theoretical system around the case for homosexual emancipation; he determined himself on several occasions - perhaps overly so - as a "normalsexual", i.e. heterosexual. However, according to his personal diaries he was certainly not insensitive to male beauty. The tracks he left are difficult to trace, since - in the words of Hungarian writer, Ferenc Móra in 1936 - "With him Wahrheit und Dichtung (reality and fiction) are very much mixed up: he is often mistaken when talking about others but he is least reliable when referring to himself".

Kertbeny's figure was distinguished by these dualisms. His adventures can be interpreted as multiple identity seeking attempts that he could not avoid because in the era of 19th century monolithic identities, due to the lack of social acceptance, he was not Hungarian enough, not literary enough, and perhaps not even "normalsexual" enough.

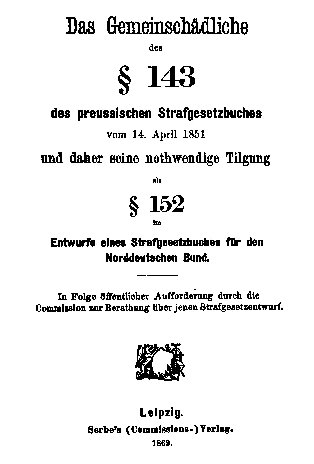

Kertbeny wanted to be successful and create something lasting in literature. However, nowadays we can remember him primarily because of the novelties in sexual terminology he created: he was the one who coined the expressions homosexual and heterosexual in the late 1860s, as uncovered by the German researcher, Manfred Herzer.

Today, many perceive the word homosexual to be a medical term, mainly because of the fact that from the late 19th century until the 1970s this expression was monopolised by the medical approach interpreting same-sex attraction to be a pathology, degeneration or illness. Still, it is important to remember that Kertbeny introduced the word homosexual in the course of the struggle for homosexuals' rights in a surprisingly modern human rights argumentation.

Kertbeny did not seek biological arguments to use for the liberation of homosexuals, - i.e. a relatively small social group with limited power to further their own interests - instead, he made the point that the modern state should extend the principle of not intervening in the private lives of citizens to cover homosexuals, too:

"To prove innateness ... is a dangerous double edged weapon. Let this riddle of nature be very interesting from the anthropological point of view. Legislation is not concerned whether this inclination is innate or not, legislation is only interested in the personal and social dangers associated with it ... Therefore we would not win anything by proving innateness beyond a shadow of doubt. Instead we should convince our opponents - with precisely the same legal notions used by them - that they do not have anything at all to do with this inclination, be it innate or intentional, since the state does not have the right to intervene in anything that occurs between two consenting persons older than fourteen, which does not affect the public sphere, nor the rights of a third party."

Looking back almost one and a half centuries we can state that the case made by Kertbeny helped a significant, modern social movement - the struggle against the discrimination of those who enjoy same-sex relationships - to emerge.

I believe that the inauguration of Kertbeny's new tombstone today also serves to remind us - and others, too - of the importance of struggling against any form of unlawful social discrimination.

Today's celebration honours Kertbeny - and all those who stand for the respect of human dignity. The fact that we are here, that this celebration could be realised is the mark of solidarity that can give us strength and of which we can rightly be proud. This pride does no harm, rather it brings us closer together. We thank and acknowledge all who dared and still dare to be proud!

Judit Takács

29th June, 2002